This guide will show you how to start a poem in five simple steps. But it will also do so much more than this. As a former English Literature student, I learned how to start a poem at university.

I was guided by lecturers and read classic poetry extensively as part of my training. As a result, I have written many poems over the years, primarily about travel, something that is a personal passion of mine.

In this guide, I will provide some simple steps that anyone can follow. If you’ve never written a poem in your life, you can use my advice and guidance to get your first words down on the page.

As well as my own experiences, I draw on and interpret the works of classic poets like Shakespeare, Burns, and Whitman to show you how to start a poem.

Sound good? Join me and discover the steps you need to follow to master the art of poetry.

How to start a poem – Formatting steps & rules

Poetry doesn’t follow any rules. You have carte blanche when writing a poem, and it can be as long or short as you like. It might rhyme, but it doesn’t have to. The beauty of poetry is that the writer is in complete control of its form, style, and rhythm.

That said, there are specific types of poetry that follow specific conventions. For instance, the sonnet is perhaps the most formulaic type of poetry, consisting of 14 lines with 10 syllables per line. So, if you prefer following a particular format, the option is there.

As you learn how to start a poem, you might find it useful to follow the same steps that I do when writing in my spare time. I spent some time formulating the process that I follow, which I have summarized in the following five steps below:

Step 1: Decide what to write about

I find that one of the most challenging aspects of how to start a poem is deciding what to write about. This is the beating heart of any poem, and as the writer, you need to be confident in your topic and theme.

Historically, most poems were written about love. But more broadly, poetry is perfect for conveying strong emotions or ideas. It can also be used to write about specific historical events.

For example, two of my all-time favorite poets are Wilfred Owen and Siegfried Sassoon. Both men were poets during the Great War, writing perceptibly about the horrors around them. Owen’s Dulce et Decorum Est is undoubtedly one of the most emotive poems ever written, and it has nothing to do with love.

If you’re really struggling with what theme to pursue in your poem, consider some of the following ideas to set the creative juices flowing:

Love

Look no further than the Shakespearean sonnets if you want to write about love. You can explore everything from heartbreak to eternal love and there are so many variants to entertain. Whether they are love poems for her or him, writing this type of poetry is a great way to get a weight off your chest.

Even if your poem isn’t explicitly about love, it might be a sub-theme that you touch upon (your love of nature or your appreciation of the vastness of space, for instance).

Other examples of love poems for inspiration

- A Red, Red Rose by Robert Burns.

- Shall I Compare Thee to a Summer’s Day (Sonnet 18) by William Shakespeare.

Death

Historically, many poets wrote about death as a way of dealing with a tragic loss. This is perfectly illustrated in Sylvia Plath’s Lady Lazarus, a poem that dealt with the horror of death at Nazi hands. Some people find solace in writing personal odes or poems when they lose a loved one.

This could, perhaps, be the ideal way to say goodbye to someone at their funeral. You could compose a short, sentimental poem reflecting on the joys of life before death took your loved one.

Other examples of death poems for inspiration

- On the Death of Anne Bronte by Charlotte Bronte.

- If I Should Die by Emily Dickinson.

Nature

The natural world provides a boundless source of inspiration for poets. From the high Himalayas to the wind-swept sands of the Sahara, there are so many ways to explore the natural world through words. William Wordsworth was a master of nature poetry, as was Rudyard Kipling.

The Way Through the Woods by Kipling is one of my all-time favorites, but I also recommend The Tyger by William Blake. Both poems present the ideal foundation if you’re keen to draw on nature as the main theme in your poem.

Other examples of nature poems for inspiration

- Spring by William Blake.

- It is a Beauteous Evening, Calm and Free by William Wordsworth.

Travel

If you’re looking for an exciting theme for your poetry, travel is a great option. The legendary writer of the Lord of the Rings, J R R Tolkien, wrote a brilliant poem about travel, The Road Goes Ever On, which interlaces travel, death, and the boundless enthusiasm many have for life.

Many contemporary poets have also written about travel, including the brilliant For the Traveler by John O’Donohue, which is an introspective look into the reasons why so many of us embark on the open road.

Other examples of travel poems for inspiration

- Eldorado by Edgar Allan Poe.

- Song of the Open Road by Walt Whitman.

Poets tend to focus on the big picture topics in their work, as you can see from the above examples. You don’t have to be too prescriptive, but starting with a general theme in mind will help to guide your creativity as you learn how to start a poem.

Step 2: Consider which format to follow

After exploring some of the common themes of poetry, it’s time to think about the format your poem should take. As I mentioned at the start, you don’t have to follow any specific rules if you don’t want to. That said, some poets find it helpful to write with an established format in mind. Some of the popular poem formats you might consider include:

Sonnet

One of the most famous types of poem, the sonnet, was popularized by William Shakespeare, though it has its origins in Italy. Sonnets are written across 14 lines with four verses. The first three verses are quatrains, with four lines apiece. The final verse has two lines.

While there are different rhyming conventions, Shakespearean sonnets tend to follow an A-B-A-B C-D-C-D E-F-E-F G-G format. Also, iambic pentameter is typically used in sonnets, with ten syllables per line – more on this later.

Haiku (Hokku)

The haiku is an ancient type of Japanese poetry that has enjoyed a renaissance in recent years. There are just three lines in a haiku. The first and third lines should have five syllables, while the second line should have seven.

They’re extremely fun to put together and are often written about mood or emotion. You can play around with different words, safe in the knowledge that haikus don’t always have to rhyme.

Free verse

If you want to write a poem without prescriptive rules, free verse is the way to go. As the name suggests, feel free to mix it up!

You don’t have to worry about syllables per line or whether the poem follows a special rhyming scheme. This is the perfect format for anyone who views the rules associated with sonnets as suffocating to their creativity.

Villanelle

While free verse poems have no rules, the Villanelle has the most prescriptive set of rules. This type of poem was popular in France and comprises 19 lines, with five stanzas of three lines. The final stanza should be a quatrain (with four lines).

Only two rhyming sounds are permitted throughout the poem, as it follows an A-B-A A-B-A A-B-A A-B-A A-B-A A-B-A-A format. Repetition is also key throughout, with line one also serving as lines six, twelve, and eighteen.

Limerick

We have English poet Edward Lear to thank for the limerick. For instance:

There was a Young Lady of Russia,

Who screamed so that no one could hush her;

Her screams were extreme,

No one heard such a scream,

As was screamed by that Lady of Russia.

Just brilliant! Limericks are light, upbeat, and usually humorous. They’re short, with just five lines and a rhyming scheme of A-A-B-B-A. Most poets who write limericks ensure the final line is a punchline of sorts, much like the punchline of a joke. This type of poem is great if you don’t want to deal with the more serious themes of conventional poetry.

Ballad

Ballads were common throughout the Middle Ages and were often accompanied by music. In fact, many of the songs that we hear today in popular culture are contemporary forms of ballads, particularly love songs. This is a long, often intense type of poetry that loosely follows an A-B-A-B or A-B-C-B rhyming scheme, though not all ballads rhyme.

When considering how to start a poem, it’s really helpful to know which type of poem you want to write from the outset. Although you can change or even break the rules of various poem types, it helps to use the conventional format and rules to guide you as you write. If you don’t want to follow specific rules, write in free verse.

Step 3: Experiment with free writing

If you sit down and decide you want to write a sonnet or a haiku, you might restrict your creativity. After all, these formats require you to follow strict rules and conventions, which can stifle creative expression.

So, even if you want to write a sonnet or a haiku, I recommend writing freely to begin with. This is the art of getting your ideas down on paper in front of you. Write in fluid prose or shorthand and list rhyming couplets if you think this will help.

The idea is to explore your chosen theme freely without being restricted by convention or form. Then, when you have a page of notes, doodles, and ideas down in front of you, it’s much easier to format your poem. Though this approach doesn’t work for everyone, it’s worth trying if you’re struggling with how to start a poem.

Also, if you’re really struggling with the right words to use, you can sign up for our Poem Generator to help you.

This handy tool will help you to create a poem in seconds. Though you don’t necessarily need to publish the first draft, it can help formulate ideas and provide a brilliant foundation for your work. It’s free and easy to use, so dive in today if you’re suffering from writer’s block.

Step 4: Explore the poem’s sound and rhythm

When writing poetry, you will quickly realize that the poem’s sound and rhythm are just as important as the words you include.

The rhythm of a poem is essentially its beat. Therefore, the words you use are crucial, as they influence the flow of the final product. Understanding the difference between stressed and unstressed syllables will also help you master the flow of a poem.

Understanding iambic pentameter

Though a technical term, I encourage you to think about iambic pentameter when writing poetry if you want to improve your flow and rhythm.

Here’s a simplified breakdown of what it means:

- In poetry, iambs are units of two syllables. The first syllable is unstressed, and the second syllable is stressed.

- Pentameter is a type of verse that consists of five metrical feet per line. Pent, in ancient Greek, means five.

- When brought together, then, iambic pentameter is the art of using ten syllables in five metrical feet per line, something Shakespeare so often did in his sonnets.

Iambic pentameter example

Let’s look at the first line of Shakespeare’s Sonnet 18 as the perfect example of iambic pentameter in action:

Shall I | comPARE | thee TO | a SUM | mers DAY?

1 2 3 4 5

While you’re not required to write in iambic pentameter, it’s a really useful literary tool that helps to regulate the flow of your work. It can also help with rhyming, another thing to consider when learning how to start a poem, as I explain below.

Rhyming sounds

Let me start here with a caveat – your poem does not need to rhyme. Some of the best poems of all time were written in free verse with complete disregard for the rules and regulations relating to rhyme. Look no further than Walt Whitman’s masterpiece, I Hear America Singing, as the perfect example of this.

But, at least in my opinion, rhyming poems are much easier to read. They are also much more fun to write, as much of the thrill of poem writing lies in your ability to find suitable rhyming couplets.

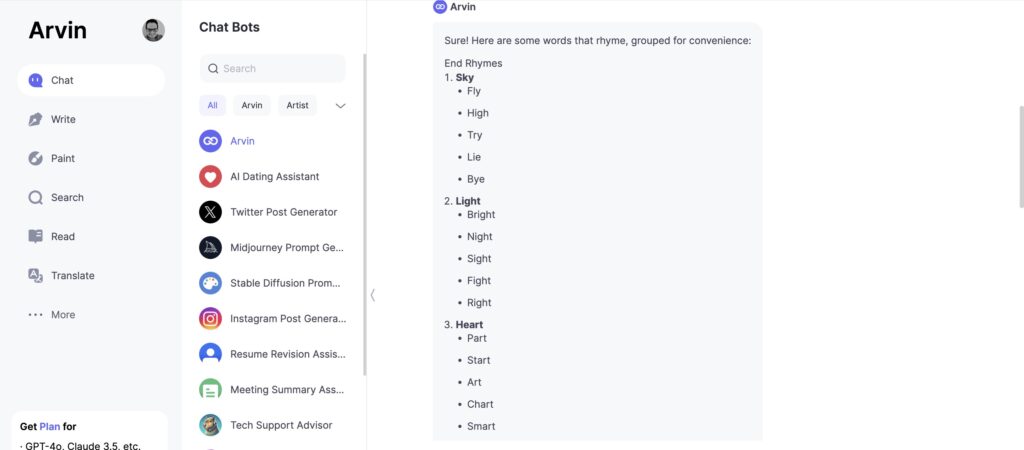

When you’re struggling at the beginning and learning how to start a poem, I recommend listing as many random rhyming words as you can. This should only take a few minutes, but it will help you enormously as you work on your poem.

If you don’t want to do it yourself, ask Arvin to list some rhyming words, as I did in the following example:

You can then use these words at the end of your respective lines when you’ve decided which rhyming pattern you want your poem to follow.

Step 5: Complete the first line

So, with the previous four steps behind us, all that’s left is to write the first line of your poem. This doesn’t need to be as daunting as it sounds.

If you practice free writing, look at some of the things you’ve written down on the page in front of you. Can any of these sentences be crafted into the perfect opening line?

You can always change the poem’s first line later, but getting something down is crucial to avoid writer’s block.

Again, if you’re staring at a blank page, consider asking Arvin to create a first line for you. You can also read our guide to poem themes and ideas if you’re struggling to kick things off.

How to start a poem – draw inspiration from these famous poets

As I bring this article to a close, I want to remind you that there’s an entire world of poetry out there, just waiting to be discovered. While I caution you not to plagiarize anyone’s work, you absolutely should draw on famous writers for inspiration.

If you’re new to poetry, I advise you to read the work of some of the following writers, depending on the theme you’re interested in. This is far from an exhaustive list. But I handpicked my favorite poets that I encountered during my study of English Literature at University – I hope you find it useful:

- Love: Robert Burns, William Shakespeare, John Keats, Lord Byron.

- Death/Anguish: Sylvia Plath, TS Eliot, Emily Dickinson.

- Classics (ancient poets): Rumi, Homer, Sappho, Dante, Li Bai.

- Nature: Walt Whitman, Mary Oliver, William Wordsworth, Edgar Allan Poe, William Blake.

- Society & Culture: Robert Browning, Rudyard Kipling, Robert Frost, Mark Twain.

- Feminism: Audre Lorde, Adrienne Rich, Edna St. Vincent Millay.

- Civil Rights: Langston Hughes, Maya Angelou.

- War: Wilfred Owen, Siegfried Sassoon.

As I have listed these writers thematically, I hope they will inspire you as you learn how to start a poem. You can dip into some of their most famous poems and take inspiration from their words – I certainly have done this in the past!

Final words: How to start a poem to master the art

Learning how to start a poem will stand you in good stead if you want to master this literary art form. Though many see poetry as a lost art, I regard it as a brilliant way to express yourself. Writing poetry is a wonderful skill to learn, much like writing music.

It can channel your inner creativity and lead you to express your feelings in pure and insightful ways. Whether you plan on publishing your poems is entirely up to you. As I’ve shown above, there are so many ways to start your poems, and you can follow or break the rules as you see fit.

But if there’s one takeaway to remember, it’s this – draw on the classics for inspiration. Read poetry widely before writing some yourself. This will help you enormously. You can also rely on Arvin’s AI tools and prompts to guide you if you’re suffering from writer’s block.

How to start a poem FAQ

What is a good sentence to start a poem?

This is a very difficult question to answer, as practically any sentence can feasibly start a poem. That said, your opening line should be engaging and alluring. It should foreshadow the rest of the poem, if possible, and set the theme and tone.

What is a good starter for a poem?

Some poets begin their work by addressing the reader – this was actually very common in the past and is a literary technique you might wish to copy. In my experience, starting a poem with a descriptive sentence works particularly well, given the exploratory nature of most poems.

How to start a poem that people want to read?

Remember, there are so many different forms and styles of poems that the way you start it will depend on what you’re hoping to achieve. Still, where possible, your poem should start confidently and it should be relevant to the rest of the piece. If you’re struggling with the opening line, leave it until later. You can always come back to the first line when your poem is complete.